The Complete Man Equation

Throughout human history civilizations have risen and fallen. What starts as a small tribe or gang of men and women seeking to fulfill their basic needs and survive, turns into a bustling society of refined individuals desiring to live by a higher set of ethics which will guide their morality. Then something is the catalyst for that civilization's downfall and the fragments which are left behind become small, roaming bands of men and women seeking to survive once again; and the cycle continues.

During the periods of building up a civilization and the maintaining of civilization, men’s roles shift in their focus.

When survival is all that matters, men are generally concerned with protecting the perimeter of their small tribe, providing the majority of its food, and procreating children for the purpose of building the tribe’s strength. Every man needed to step up and fulfill these roles because if he didn’t, his people suffered; they would never be able to resist disease, famine, natural disasters and other warring tribes if he faltered in his duties.

When that tribe grows large enough however, and becomes more “civilized,” men’s focus generally shifts to how they fit into the society they have created and seek to abide by the rules and set of morals established in that culture's structure. Since their basic needs and the needs of their people are being met, they are afforded more time for philosophical contemplation about what is good, how to be good and why to be good.

In short, there is a shift from being good at being a man to being a good man.

The Times In Which We Live

Currently here in the US and in many parts of the world, we have the opportunity to enjoy the peak of civilization in human history. Never before has there been so much comfort and ease. Naturally then, since our basic survival needs are met, most men are not required to be the same protectors, providers and procreators as when survival was not guaranteed; there is not a desperate need for such men when everything is relatively easy.

Because of our lack of tangible danger and real physical struggles, all our focus has naturally shifted, and being good at being a man has become more and more neglected.

Our concern, like other civilized societies throughout history, gradually shifted to how to be good men. We concentrate our personal improvement efforts almost exclusively on how well we abide by the code of ethics and morals laid out by our culture and how we can rise above our natural, base tendencies towards overindulgence, laziness, selfishness, etc. As a result, countless religions, self-help books and entire movements are dedicated to helping men be more good.

On Being Good at Being a Man

But perhaps John Wayne put it best,

“You have to be a man first before you’re a gentleman.”

While it is true there is no longer a compelling requirement to be good at being a man in our day and age, the pursuit of it is still valuable.

In my own life I have felt something lacking in simply pursuing being a good man at the expense of being good at being a man. While it is desirable to strive to be a good man— and I believe it is necessary to truly be the best I can be— it somehow feels… hollow. Almost like empty talk.

In one of their most comprehensive articles, Brett and Kate McKay from The Art of Manliness shared this perspective on the matter:

“...seeking to become a good man, while completely ignoring the pursuit of becoming good at being a man, does create a couple of problems. First… developing your physical strength and capacity to fight facilitates the attainment of higher and more spiritual virtues. By neglecting being good at being a man in favor of being a good man, you ironically stymie your pursuit of virtue. To achieve true eudemonia, we should seek to exercise our innate characteristics, while also expanding our higher spirit. Second, a man’s claim to virtue is weak if he doesn’t have the virile fortitude and strength to back it up when challenged. The cloak of virtue hangs very awkwardly on a man without fire and fight; it droops and sags when draped across a structure that lacks strength and firmness. We all know amiable men who are sickly thin or grossly overweight, who look like they’d burst into tears if a bully broke their walking stick and would get winded mounting a flight of stairs. These mealy men profess to be nice guys, perfect gentlemen, but we don’t respect them as men.”

I could be the nicest, most pleasant guy out there, but if I couldn’t protect my wife against an assailant, isn’t all that niceness, pleasantness and “goodness” ultimately wasted? If I do not possess hard, practical skills will I be the guy you want on your team when there is an emergency? Need help with your car that just broke down? Or perhaps an extra hand with some repairs around the house? How about an active shooter that just entered the building?

Chances are in these scenarios, I wouldn’t be the guy you’d rely on. Why? Because when the rubber meets the road, when the pedal hits the metal, I’m not an asset— which effectively renders me useless. And does that not make those higher virtues somewhat pointless in the end?

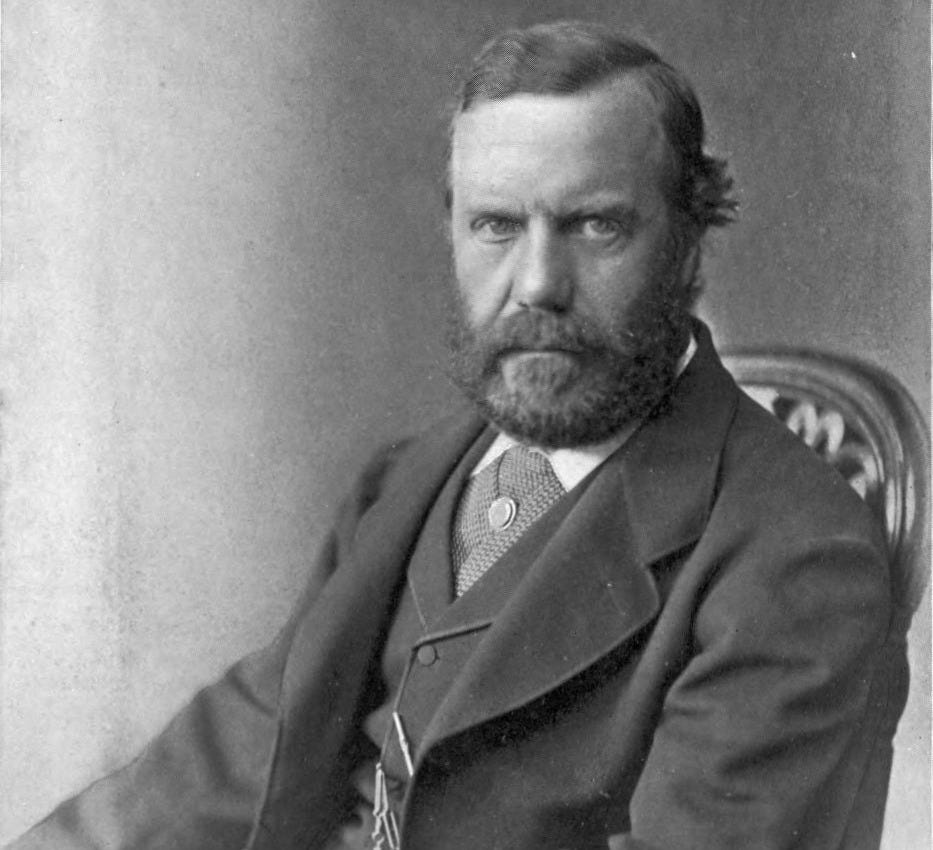

Teddy Roosevelt had this to say:

“Over-sentimentality, over-softness, in fact washiness and mushiness are the great dangers of this age and of this people. Unless we keep the barbarian virtues, gaining the civilized ones will be of little avail.”

The civilized virtues are less useful when the barbarian virtues are not the base which they are built upon; without a firm foundation to stand on, the higher virtues crumble and crack. What may have been kindness, pleasantness, and gentleness are as Roosevelt described, “washiness, mushiness and over-softness.”

Let’s consider this analogy to illustrate the point:

Picture a guy with a grape. He is literally unable to crush the grape no matter how hard he tries because he does not possess the raw strength capable of crushing it. Could that man be considered gentle? No. He is weak. In order to be gentle one must first be strong.

It is the same with the higher, civilized, refined virtues, and the hard, practical, tactical, barbarian virtues. Without the latter, the former cannot truly exist.

From a pure survival standpoint, unless there are males who are good at being men to defend the perimeter of their group, then civilization cannot even be built and being good men will not even be possible.

Jack Donovan in his book The Way of Men takes it one step further and says, “A man who is more concerned with being a good man than being good at being a man makes for a very well behaved slave.”

Additionally— whether it is a right or wrong perspective— being a good man can unfortunately be somewhat subjective if we take a broad, worldwide view. Every religion, culture, and creed is going to have differences in what they consider a “good man”— which can range from small variances to entirely opposing viewpoints.

If the definition of a man is based solely off of a culture’s current idea of ethics, then masculinity, manhood and manliness can be anything. And if it can be anything, it may as well be nothing because it becomes so watered down it effectively loses its meaning.

(While this raises an interesting debate on whether moral principles are absolute and universal to all people, as opposed to relative to every individual, it is a conversation which deserves it’s own devoted article and won’t be examined here.)

Being good at being a man however, can be more objectively observed.

In his book, Donovan outlines four amoral virtues which men tend to hold the other men in their gang or tribe accountable to. These amoral virtues— strength, courage, honor, and mastery— are expected to be consistently demonstrated by the men in the group because it shows their capability. If a man is able to consistently display them it means he is a reliable asset to the group’s survival.

Am I good at being a man (i.e. demonstrating strength, courage, honor, and mastery in the face of adverse circumstances)? No? Then I can’t be counted on when the proverbial crap hits the fan; I am a hinderance and a hinderance in an emergency is just as dangerous as a threat.

Donovan goes on to clarify though, and says that what truly matters is for a man to show a willingness to display said virtues and then acting on them in any way he can. Even if he falls short in some aspects, such a man is more valuable than the man who completely shuns manhood altogether and endangers the group through his “flamboyant dishonor.”

Although it seems harsh to judge another man thusly— especially given our culture’s infatuation with not hurting feelings— it serves the purpose of discerning which men are truly worth their salt; which men are worthy of our respect. (It might be a controversial statement, but not everyone is worthy of respect just because they demand it.)

We inherently are drawn to the man who proves himself capable and strong because we find these traits admirable and beneficial, and the man who possesses them sets himself apart from the rest.

Not all our relationships need be completely utilitarian in nature, but for our purposes the above arguments prove the point that being good at being a man is objectively measurable; that type of man is not rooted only in the subjectiveness of his culture’s idea of a good man, prone to alteration when the winds of change blow. Rather, one’s identity as a man can be firmly planted on the solid ground of whether or not he is objectively meeting the standards other men will hold inevitably him to— standards which haven’t changed much since the dawn of humankind.

It behooves us as men then to develop this side of ourselves— for our own personal betterment and the betterment of those around us and in our care. Being good at being a man gives us purpose. It shows that we are worth something. We are valued and, contrary to popular media, as men we are needed by society. Our purpose as men is to be useful in the fulfilling of our masculine roles to the best of our given ability in this modern world, and being useful in our masculine roles gives us purpose as a man.

On Being a Good Man

Obviously, we cannot neglect the pursuit of being a good man entirely in favor of being good at being a man though.

Being a good man gives our life significance. We learn there is more than ourselves and our base desires; and our lives become more full as a byproduct. We can find value in the conquering of our faults and weaknesses; and through the betterment of ourselves our relationships become rich and alive. In short, we leave a good impact on those who we come into contact with. The significance of our lives as men is directly correlated to how much good we have added to the world and the people around us and we do goodness through the development of morals, virtues and ethics.

If men do not seek after developing and abiding by a set of morals, virtues, and ethics then as the saying goes, “boys will be boys.”

Males can be stupid, reckless, ego-driven, and downright violent at times due to a lack of self control or restraint. History is full of stories of men who were not good and sought to gain by being usurpers. There’s a reason stereotypes of masculinity exist which are often labeled as “toxic” after all; men like these give the rest of us a bad name.

Without a code of morals to abide by however, it is still entirely possible for a man to be good at being a man and not be a good man— although this path is much less encouraged than the alternative. While he might be the person you want by your side when you’re in the thick of combat and the bullets are flying, your wife doesn’t feel comfortable around him and he is not a shining example to your children.

Worse than simply neglecting to develop ourselves into a good man however, is the abandonment of a higher, nobler aim at all. Men in our society today are more and more at risk of becoming completely apathetic. In the presence of one’s ability to engage in snug idleness, manliness is slowly eroding away and a man’s morals are increasingly becoming a grey area. Suddenly one’s conception of what it means to be a good man isn’t just different from previous generations, it is ambiguous; and it is hard to hold fast to your principles when your principles aren’t clearly defined. If a man has no code of ethics which will govern his choices, the same man in the absence of the need to survive will eventually just become bored and succumb to his base desires for pleasure and amusement.

Couple this ambiguity with the rampant distraction a man may face today from his phone, social media, video games and the satisfaction of ease, comfort and highly palatable foods and beverages, and he faces becoming fat and slothful— not just physically and mentally, but spiritually and morally as well. These distractions only succeed in pulling a man away from pursuing the noblest desires of the human soul.

Socrates once said,

No man has the right to be an amateur in the matter of physical training. It is a shame for a man to grow old without seeing the beauty and strength of which his body is capable.

Could not the same also be said for a life lived according to a set of principles— that no man has the right to be an amateur in the matter of virtuous living? Because it is indeed a shame for a man to grow old without seeing the beauty and strength of which his character is capable.

Yet this the edge at which we are all teetering; we first opted as a society to neglect the pursuit of being good at being men in favor of only pursuing being good men and now we may very well find ourselves careening into the abyss of abandoning pursuit altogether.

The Complete Man

If we are to become men of the most noble, bold, strong, and honorable quality then we must not only reengage in our pursuit of one of these paths, but resolve to pursue both with dogged conviction; by living our lives in accordance with “The Complete Man” equation.

Being good at being a man + Being a good man = A complete man.

This I believe, should be our ultimate goal.

While the practical application of how we go about putting this equation to use may differ due to the unique circumstances of every man’s life, here are some suggestions:

Being Good at Being a Man:

Develop your physical strength.

Create or join an honor group of likeminded men.

Learn how to defend yourself and loved ones by learning to fight.

Compete against other men in sports and games.

Become capable in nature and learn survival tactics.

Be prepared by building an emergency kit that you always keep in your car.

Develop your physical toughness and mental fortitude by pushing outside of your comfort zone.

Be the main bread winner of your family.

Have kids and craft a legacy to pass on.

Identify ways to be more useful to other people.

Create more than you consume.

Being a Good Man:

Develop civility in your interactions with everyone and give people the benefit of the doubt.

Write down what your beliefs are and, more importantly, why they are your beliefs.

Read more books.

Faithfully adhere to a religion or spiritual doctrine of your choosing.

Follow Benjamin Franklin’s example and define your core virtues.

Cultivate silence in your day by disconnecting from technology.

Practice temperance by following a diet.

Exercise discipline and willpower when no one is looking.

Be chivalrous to your wife, girlfriend, or romantic interest. (No, it is not dead, and no, it is not because they are in some way inferior).

Tell the truth in a situation where lying is easy.

Identify that which you feel is right. Defend it ardently, yet be willing to admit when you are wrong.

Conclusion:

Identifying and differentiating between these two sides of the equation will hopefully allow each of us to become more complete men and to fight back against the entropy of our manhood and the degradation of our society. Hopefully, by this point you also agree that neglection of either side is undesirable, and a complete abandonment of it is deplorable. If we choose to reengage in worthy pursuit, our lives will increase in both significance and purpose and we will find ourselves the better for it.

Let’s move forward following the admonition of Theodore Roosevelt Sr.’s advice to his son: “I was always to be both decent and manly, and that if I were manly nobody would laugh at my being decent.”

And likewise with TR Jr.’s vision of the ideal American boy,

When I speak of the American boy, what I say really applies to the grown-ups nearly as much as to the boys…I want to see you game, boys; I want to see you brave and manly; and I also want to see you gentle and tender. In other words, you should make it your object to be the right kind of boys at home, so that your family will feel a genuine regret, instead of a sense of relief, when you stay away; and at the same time you must be able to hold your own in the outside world. You can not do that if you have not manliness, courage in you. It does no good to have either of those two sets of qualities if you lack the other. I do not care how nice a little boy you are, how pleasant at home, if when you are out you are afraid of other little boys lest they be rude to you; for if so you will not be a very happy boy nor grow up a very useful man. When a boy grows up I want him to be of such a type that when somebody wrongs him he will feel a good, healthy desire to show the wrong-doers that he can not be wronged with impunity. I like to have the man who is a citizen feel, when a wrong is done to the community by any one, when there is an exhibition of corruption or betrayal of trust, or demagogy or violence, or brutality, not that he is shocked and horrified and would like to go home; but I want to have him feel the determination to put the wrong-doer down, to make the man who does wrong aware that the decent man is not only his superior in decency, but his superior in strength. (Emphasis mine).